So I have absolutely no idea why I came home feeling kinda dejected.

There's no reason for it at all. Except that preaching is this profoundly paradoxical endeavor that can leave you emotionally energized and emotionally drained, spiritually blessed and spiritually broken, intellectually stimulated and intellectually wrung-dry, all at once. I read this preacher once (think it was William Willimon), who said something like: No one who has really felt what it is to preach the word of God will ever feel like they've really done it.

And that says it for me.

I've shared different thoughts about the nature of preaching over the last few months (like here or here). Reflecting back over yesterday, I'm wondering again: what is it that makes preaching preaching? What separates this speech-act from other kinds of public oration-- lectures, speeches, philosophical pontification, dramatic performance?

My friend David talks a lot about the radical assertion made in the Second Helvetic Confession (1566), that "The preaching the word of God is the word of God." David likes to point out that what makes preaching preaching is its outrageous conviction that God himself speaks in, through and with the words of the preacher; and unless God does, preaching is one of the silliest of all human activities. That's always been helpful for me (though again it always brings me back to the above quote: No one who has really felt what it is to preach the word of God will ever feel like they've really done it.)

But today I'm remembering another word of advice a friend gave me about preaching. Preaching, he said, must be a public proclamation that depends fundamentally on the death and resurrection of Jesus to give it meaning. Put differently: would you still say what you're about to say if the cross and the empty grave had never happened? Could you still say it if Jesus was still in his grave? If the answer is yes to that question, then whatever else you're doing-- entertaining, exhorting, educating, moralizing-- whatever else it is, it's not preaching.

I think this is the vital question for the church to ask whenever there's speaking from the pulpit: Does the fact that God raised the crucified Lord from the dead matter at all to these words?

Because we could still tell each other to do more, give more, try harder, be kinder or less stressed or more self-actualized, be better parents or spouses or citizens-- all this even if Jesus was still dead. We could even still help people understand the historical context, literary conventions and grammatical structure of the biblical text, without needing a really-risen Lord.

But we wouldn't be preaching.

And until our words depend on the proclamation that God raised his crucified Messiah from the dead, and that his risen Life now beats at the heart of all our acts of Christian service, and devotion, and life together-- until our words hang with bated breath on this reality- we may always go home inexplicably dejected, feeling like we haven't preached.

Resurrection and Proclamation

Labels: preaching, resurrection

From the Grave to the Sky

The Ascension never got much press in the church tradition I grew up in. Maybe it seemed a bit too high church, maybe we felt we had our hands full enough with Christmas and Easter (and Mother's Day...). Not sure.

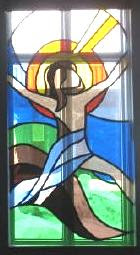

But if salvation is all about what God has done to reconcile humanity to himself and draw us up into the life of divine fellowship, then the Mount of the Ascension is an important landmark on the horizon of that story. Because it's on that sacred peak that we watch our Lord take the resurrected and redeemed flesh of our humanity into heaven, to sit at the right hand of Glory and intercede on our behalf in the Most Holy Place; and there, too, we are offered the assurance that one day he will return to us, coming in the same way we saw him go into heaven (Acts 1:11).

My friend Jon has posted some great thoughts about the meaning of the ascension on his blog here. Well worth reading and meditating on. One of the authors he quotes suggests that in terms of its theological significance, the ascension should get as much emphasis in the church year as Christmas does. Food for thought.

I heard Jon preaching a while back. He was referring to a painting of the ascension and he mentioned how hard it was for him to see it, because sometimes he felt like those apostles on that mountain top, longing for Jesus to stay. Then he said: "I know this might sound cheesy, but I wish he was here."

Now Jon's a very sincere guy; I think if anyone could say something like that without sounding the least bit cheesy, it'd be him. His words haunted my heart for a while, until I finally sat down and tried to turn them into a song. At the time I had this sad/jazzy arrangement for the song "All Heaven Declares" that I was working on, and I thought: what better way to evoke the tension between the already and the not-yet of the Kingdom, than to take a tune normally used to exult in the "already" of Christ's reign, and give it words expressing deep ache over the "not yet" of His return?

Well, it's no turkey dinner with all the trimmings, but I thought I might offer it here as a bit of an Ascension-day present. You can click here to "unwrap" it.

Every blessing as you remember the ascension of our Lord.

Labels: ascension, Jesus, songwriting

Negative Capability and the Call of the Preacher

The famous Romantic poet John Keats once said that what made the truly great poet great was something he referred to as a "negative capability." The poetic genius, he said, can negate his or her own personality in order to enter imaginatively into the reality of the other. This "negative capability" allows the poet to "[be] in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after facts and reason." In other words: because the poet has the imaginative capacity to negate his own personality, he can accept the paradoxes and conflicts necessary to great art without giving in to the rational impulse to resolve the tensions. According to Keats, the poet that offers us the best example of negative capability is Shakespeare, who could take "as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen," and feel no personal need to resolve the tension between the two.

The famous Romantic poet John Keats once said that what made the truly great poet great was something he referred to as a "negative capability." The poetic genius, he said, can negate his or her own personality in order to enter imaginatively into the reality of the other. This "negative capability" allows the poet to "[be] in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after facts and reason." In other words: because the poet has the imaginative capacity to negate his own personality, he can accept the paradoxes and conflicts necessary to great art without giving in to the rational impulse to resolve the tensions. According to Keats, the poet that offers us the best example of negative capability is Shakespeare, who could take "as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen," and feel no personal need to resolve the tension between the two.

Negative capability is one of those nebulous terms that most students of English literature will run into if they study it long enough. It was negative capability, Keats suggested, that allowed the poet to transcend himself and express true beauty in his work.

And I've been wondering these days if a certain kind of "negative capability" shouldn't also be a quality of preachers, too. Sometimes preachers are lauded for preaching from "where they're at," for preaching from the heart, for displaying a certain kind of personal vulnerability from the pulpit. And I get that; and in my own preaching, too, I strive for personal authenticity. But I also remember that St. Paul commended the Thessalonian church because when they received the preached Word, they accepted it "not as the word of men, but as what it really is, the word of God." From what Paul says there (and elsewhere), the ultimate goal of preaching is the human response to the living Word of God, and emphatically not to the personalized words of the preacher.

As I struggle to figure out what that means for me as a preacher, that's when I remember Keat's negative capability.

Because when the preacher can negate his or her own personality in order to enter imaginatively into the reality of the divine other, as it is revealed in the Word she preaches-- when the preacher can "be" in the uncertainties and paradoxes of that Word without giving in to the rational impulse to personally resolve the tension she feels there-- when the preacher can exercise the imaginative capacity to negate herself in the very words she speaks-- when her preaching has this "negative capability"-- that's when she'll discover the living Word is truly speaking in her, and with her, and through her.

And that's when her gospel will come to her hearers, as Paul says, not in word only, but also in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction.

The Bad Publicity of the Cross

This idea is only half baked, so I'm fine if someone wants to tell me to put it back into the oven for a while. It's just this: the other day I was subbing for a grade 12 class and in the five minute scrum before the bell they got talking at random about the end of the world. Apparently someone had done some research into the ancient Mayan calendar that predicts the world will end in 2012. They chewed this back and forth for a while, till someone asked me, "Don't Christians say the world's going to end, too?"

This idea is only half baked, so I'm fine if someone wants to tell me to put it back into the oven for a while. It's just this: the other day I was subbing for a grade 12 class and in the five minute scrum before the bell they got talking at random about the end of the world. Apparently someone had done some research into the ancient Mayan calendar that predicts the world will end in 2012. They chewed this back and forth for a while, till someone asked me, "Don't Christians say the world's going to end, too?"

I did my best to explain: some Christians talk about the end of the world, but more accurately Christians believe in the end of the age and the resurrection of the dead, when Christ will return to establish his kingdom of peace.

One of the students sort of scoffed: "Yeah, and I believe in a plague of zombies that are going to take over the planet..."

Laughter.

I told them that they were free to laugh if they wanted to, but they also needed to know that I myself was a Christian and I shared this belief in the return of Christ.

He said: "Well, it's just that it's easier to believe in a plague of zombies than to believe in that."

From this point they started asking me what I knew about zombisim, and the conversation shifted.

But here's the half-baked thought that's been rising in my mind since this exchange. I have a feeling that if I'd shared about some esoteric belief from the Vedas, or about some mystical Nirvana experience, it would have got a better hearing than the credal belief in the Second Coming (even the Mayan calendar and Haitian Voodoo got more respect than the resurrection of the dead). And as I wondered about this, it struck me that the Vedas, the Mayan calendar, Nirvana, voodoo-- these things are all mysterious, mystical kinds of knowledge that are the special domain of the spiritual elite, kept hidden from public scrutiny. Unlike the public proclamation of the Gospel, they're spiritual secrets whispered in select ears.

And if someone's out to ridicule the faith convictions of others, these convictions are hard to ridicule because they aren't public. They're shrouded in an ambiguity that silences derision. But in the Gospel, God went public with his hidden wisdom. In the open scandal of the cross, he told the secret of his love for the creation to anyone who'd listen. He exposed it to public scrutiny.

And public ridicule.

Now this is not a typical, evangelical, "why's everybody always pickin' on me" pity-party. And I'm fully aware that there are non-Christian religious groups that our culture ridicules, some precisely because they are highly secretive; and I'm aware, too, that there was a lot of secrecy around communion and baptism in the early church, and the surrounding culture ridiculed them mercilessly for it. So my theory can't be pushed too far.

But still. I wonder if being open to scrutiny to the point of ridicule isn't fundamental to Christian faith. Because there has always been something scandalously public about following Jesus. The spiritual secrets he whispered in our ears he asks us to shout from the roof tops, in a way that makes us almost spiritually immodest next to the secrecy of many other systems of belief. Perhaps when we can humbly open ourselves this kind of scrutiny (and its attendant ridicule) without defensiveness or sanctimony, we will have really learned what it means to be followers of a crucified Lord.

Labels: eschatology, Jesus, NT

Worshiping the Fear of Isaac

There's this passage in Genesis where God gets one his most obscure, mysterious names. In Genesis 31:42, Jacob calls Yahweh the "God of his father Abraham and the Fear of Isaac." Of course there's more story here than meets the ear: no doubt it was on the mountain called Jehovah-Jireh, where Yahweh himself only just stayed the sacrificial knife held to his chin, that Isaac learned to call his father's god "The Fear."

There's this passage in Genesis where God gets one his most obscure, mysterious names. In Genesis 31:42, Jacob calls Yahweh the "God of his father Abraham and the Fear of Isaac." Of course there's more story here than meets the ear: no doubt it was on the mountain called Jehovah-Jireh, where Yahweh himself only just stayed the sacrificial knife held to his chin, that Isaac learned to call his father's god "The Fear."But of the many names for the Lord in the Old Testament, I find myself meditating on this name, Pachad Yitschaq, "Fear of Isaac," most often. It reminds me that, for all his being the Lover of my Soul, there is still something about God that is absolutely other, absolutely transcendent, absolutely the stranger. He is wrapped in thick darkness even as he is robed in unapproachable light (see Psalm 18:11 or 97:2). And for the ancients, the merest brush with the absolute otherness of God didn't come without a sense of absolute terror.

I think we need this reminder that our Father in Heaven is also the Fear of Isaac. Partly because it reminds us again what an awesome blessing we have in Christ, who leads us to the foot of Fear enthroned as to the knee of a loving father. But more importantly, because it chastens us whenever our attitudes towards God are too flippant, whenever our worship of God is too human-centred, whenever our talk about God is too self-assured. Maybe fear is one of the ways God convinces us that he is not just a spiritual self-help book or a linear equation to be solved. Because to call God "The Fear" is to confess that God is not at the beck and call of our felt-needs, or our emotional appeals, or our rationalistic proofs for why God has to be the way we want God to be.

A couple of years ago I was thinking about all this, about what it means to name God "The Fear of Isaac." Eventually my thoughts became a poem which later became a song. Wondering again about the otherness of God, I thought I'd share it here. [You can click here to listen to the song.]

Labels: OT, songwriting, worship

Running and the Art of Storytelling

I'm not really that much of a runner, but I like the half-hour of real loneliness it gives me. And I like the world all misty and gilded at sunrise. And I like the feeling of aliveness that lingers in your chest for the rest of the morning.

And I like the way it reminds me of the power of storytelling.

See, usually at some point in the run my brain starts telling me to quit-- turn back, cut it short, walk it off-- give it up kind of talk. And (true confessions) often at that point when the give-it-up-talk is strongest, that's when I start telling myself a story. The details vary, but in this story I'm the hero in some dramatic struggle, and--and here's the thing-- it all depends on me finishing this run on time.

Sometimes I pretend I'm Phidippides, running the 26 miles from Marathon to Athens to warn the Greeks of the coming Persian attack-- knowing that all Greece will be overrun if I don't make it.

Sometimes I pretend I'm Strider, running after the band of Uruk-Hai that kidnapped Pippin and Merry-- knowing that my friends will be tormented in Sauron's stronghold if I give up the chase.

If the quit-talk is especially loud, I pretend I'm Frodo running with the One Ring, in that scene near the end of his journey when he was disguised and running with a band of orcs across Mordor-- knowing that the whole world will go up in a spout of darkness and horror if I stop running.

But here's the thing: as silly as they make me feel, these little story-telling exercises really work. They push me. They get me to the end of the path. They help me feel that it's not just me puffing along alone in a Moose Jaw park at 6 in the morning, but I'm caught up in a bigger, richer (albeit in this case, imaginary) plot that gives it all meaning.

I need these running reminders about the power of story. Because I think in a way we're all looking for a story like that for life, too. A dramatic, many-layered story that lets us know that it's not just us, puffing along through the hills and valleys of life, but that we're caught up in a bigger, richer (albeit in this case, more true than true) plot that gives it all meaning. A story that calls us put down the next step, and the next, even when our hearts and brains are screaming at us to quit.

This is the story, maybe, that Jesus came to tell, and live for us, in his life and death and resurrection. This is the story, maybe, that he invites us to join him in living by the power of the Holy Spirit. And what races would we run if we let that story get us to the end of the path?

The Sound of Christ's Hand Clapping

I used to work with this guy who styled himself as a pseudo-Buddhist. I'm not really sure why; he didn't study the teachings of the Buddha or meditate or anything. I think the extent of his spiritual training was a second or third viewing of Seven Years in Tibet. But one day he told me this story, which he claimed was an old Buddhist zen.

Two monks were walking along the road, the wise master and his young initiate. As part of their ascetic training, both had taken vows of celibacy so strict that they were not even to speak to a member of the opposite sex. But as they walked along, the road brought them to a river, where there stood a beautiful young woman needing to cross. Without a word, the wise master picked up the woman and carried her across the river, set her down and returned to the other side. The two monks went on their way.

But as they walked along now, the old master could tell that his young initiate was deeply troubled by something. They continued in silence for many hours until the master finally inquired gently: My son, I see something is troubling you. Please, tell me what it is.

Father, only this: we have taken vows that we would never even speak with a woman, and yet you, you carried that woman across the river.

My son, said the master, I carried her across the river. But you have been carrying her ever since.

I've no idea where this story really came from, but, Buddhist or not, I've thought about it off and on over the years. It's not much, but there's something in there about the inner burdens we carry, or the outward facade of asceticism we try to put up when the whole time our hearts are decadent or dissipated, or the necessity of letting go of those soul-conflicts that are easier to relive again and again and again...

Sometimes I offer it enigmatically (and playfully) to my students when they're complaining melodramatically about some teacher who gave them poor grades, or some group project that bombed because their teammates weren't pulling their weight, or some crush that jilted them. And it's quite remarkable to see how they quiet and think (usually with a quizzical grin on their faces).

But these two Buddhist monks have been on my mind these days as I've been thinking about wisdom and proverbs. Because when I remember them standing there at the riverbank, master and initiate, they make me wonder: when is it right for Christians to draw wisdom from wells other than their own? And is the drinking less wise for it having come from an un-Christian well?

Our Rabbi once said that Lady Wisdom is justified by all her children: so perhaps when wisdom bubbles up in unexpected or un-Christian places like these-- in the "godless" screenplay of a thought-provoking film, or the "secular" lyrics of a prophetic rock song, or an un-Christian story about some enigmatic Buddhist monks-- perhaps we should see this as a sign that our God, the immortal, invisible, only-wise God, has not abandoned the "godless," "secular," "un-Christian" corners of our world. And perhaps the true children of True Wisdom should name these springs of unexpected wisdom, and justify them as the prevenient work of Christ, the one to whom, like Queen Sheba to Solomon, all the nations of the earth will stream at the end of the age, to marvel in person at the Wisdom of God.

On Proverbs and the Relativity of Wisdom

When I was growing up in the Faith, one of the claims I sometimes heard about the Bible is that you could tell it was God's word because it never contradicted itself. Sometimes this claim was attended with great fanfare: "Written over the course of 2000 years by dozens of different authors, and not a single contradiction!" Sometimes it was presented as a simple if-then: if it's the word of God then it must be true through and through, therefore it can't have any contradictions.

When I was growing up in the Faith, one of the claims I sometimes heard about the Bible is that you could tell it was God's word because it never contradicted itself. Sometimes this claim was attended with great fanfare: "Written over the course of 2000 years by dozens of different authors, and not a single contradiction!" Sometimes it was presented as a simple if-then: if it's the word of God then it must be true through and through, therefore it can't have any contradictions.

When they made this claim, no one ever told me about Proverbs 26:4-5. Here, in his wisdom, God tells us, "Do not answer a fool according to his folly, lest you be like him yourself." But in the very next verse he says, "Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own eyes." And just to be sure the contradiction isn't missed, the first words of both verses are exactly the same except verse 4 has a "not" and the next one doesn't.

So how should we answer a fool? Well, it depends: who's the fool and what's his folly?

Because in the contradictory tension between these two verses, I think I hear God assure us playfully that he's well aware of that secret we've been trying to keep from him ever since the enlightenment built its god-box: in matters of wisdom, more often than not the right response is "it depends."

But here God's wisdom bursts the wineskins of all our logical laws of non-contradiction, insisting that his word is not bound by those rationalistic measures of what makes it true. Dressed in a beautifully polychromatic robe, not black and white, Wisdom stands in the street unafraid to contradict herself, if by doing so she might speak true. And a good thing, too: because God also says he thinks it's abominable to justify the wicked (Proverbs 17:15); and yet, in Christ he calls himself the one who justifies the ungodly (Rom 4:5).

Holy contradiction!

Of course all this talk about true contradictions and "it depends" might have some of our relative-truth-radars beeping like mad with bogies at six o'clock! And maybe for good reason. I've heard some very eloquent and confident Christian apologists make some pretty compelling cases for absolutes in the face of relative truth.

But sometimes I think that if anyone has reason to claim that truth is relative, it's the Christian. Because our master once said that he himself was the truth-- not that he spoke true, or that he was true, or that the claims about him were true-- but that he was truth, Truth Incarnate. And if we believe he meant what he said, if we believe he spoke that word inerrantly, then whatever else we say about Truth we have to say it became a person. It's no longer known through abstract absolutes and seamless syllogisms-- it's known in relationship to a living Lord. And as we relate to this Truth who is also the Way and the Life, we discover that all the truths we cling to, to define us and set our course for life and action, are true or false only relative to him.

Learning Wisdom in the Writing

When I was learning to play guitar, my teacher gave me this advice: as soon as you have three chords under your belt, start writing songs. One of the best ways to grow as a guitarist, he said, is just start writing. Experiment with what works. Discover what doesn't. Get comfortable making mistakes, and fudging it, and making music something creative.

When I was learning to play guitar, my teacher gave me this advice: as soon as you have three chords under your belt, start writing songs. One of the best ways to grow as a guitarist, he said, is just start writing. Experiment with what works. Discover what doesn't. Get comfortable making mistakes, and fudging it, and making music something creative.

It was really wise advice.

And I'm thinking about it these days because I've been thinking a lot about proverbs (the book and the genre).

I don't think modern western Christians really know what to do with Proverbs (the book), because proverbs (as a general genre) don't live in our culture the way they might have at one time. In his book Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman describes an oral culture from Western Africa where the adjudication of civil disputes was a matter of finding in the common stock of oral wisdom the proverb that best applied to the particular case. Imagine going to court because your business partner had cheated you out of $150,000, and the judge passes sentence by referring you to the saying: "A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush." Now imagine all the parties involved (including you) left the courtroom sincerely believing that justice had been served.

Proverbs are not just catchy sayings to decorate our fridge magnets. They are ambiguous vessels of wisdom that somehow gather together and distill insightful observations about the world as it should be-- that somehow, in their utterance, actually invoke that world-- and that somehow give context and meaning for the otherwise confusing events of living. The wise application of the right proverb at the right time is a profound creative act that somehow participates in God's shalom.

And it's hard for linear, rationalistic thinking to make that kind of sense out of a proverb.

But I remember my OT prof saying once that he'd tried his hand at writing some proverbs, and I'm thinking about my guitar teacher's advice, and it occurrs to me that maybe one of the best ways to learn about proverbs is by trying to write some of my own. So over the last few days I've been trying my hand at gathering together and distilling some insightful observations about the world as it should be. And let me tell you: it's really hard. A proverb needs to ring true without cliche, needs to be pithy without being flippant, needs to be precise enough to enlighten but ambiguous enough to apply in any number of situations.

It has to sound like something you've known all along, but only just heard yesterday.

For what it's worth (and I don't think that's much) here's my list after a week or so of work. (The ones marked with a + are sayings that I've used often as a classroom teacher; the ones marked with a * are based on ideas from other sources.)

Happy is he whose heart is too big to fit on his sleeve.

He who seeks to dance alone can only dance to silence.

It is only the starving man who talks incessantly of food.+

"All I have is three chords and the truth"-- this is the fool's boast and the wise man's apology.

There is no provenience for the archaeology of the self.

The truth is in the telling when the teller is in the truth.

Wisdom crosses the desert with a stone beneath her tongue, slaking her thirst with her own saliva.*

To listen well is to find the child mature at last and the old man young again.

A good thing need not always be a pleasant thing.+

Only a hack cannot celebrate the masterpiece of another.*

When to end-- this is the second lesson of wisdom.

The true maestro is he who knows when not to play.

The question of modern art is not whether or not you could have painted it, but whether or not you did.

Only he who can manage his own website can choose to be a Luddite.

A mask may be inevitable, but not which one you'll wear.

Food for the mind and books for the body, as exercise is for the soul.

There are only four feelings-- mad, sad, glad and scared-- but O in what infinite combinations they come.

Narcissus and the writer: both alike stare into inky pools, searching for an echo of their experience.

Loving is knowing and knowing is leaving and leaving is coming back again.

The equality of unequals is inequality.+*

The only stupid question is the question left unasked.+

Sarcasm is the protest of the weak.+

Beware of both the connoisseur and the spendthrift in the marketplace of ideas. The former will buy only his brand, the later will buy anything.

Love and fear alike are a bird in a fist: to hold it hides it; to look must let it go.*

The secret to never having to stand in line is in only wanting things when no one else does.

He who fishes for truth alone will surely come home skunked.

It is impossible to say in a single picture that a picture is worth a thousand words.

Hope is a knife-edge sharpened by despair.*

Every statistic is but a mathematically narrated myth.

Only great folly shouts for silence.

Sanctimony is often the child of guilt.

The Top Five Oddest Movies I'm Glad I Can't Forget

A couple of years back, after an extended stint of picking some doozies, I was banned for a while from choosing the movie when we rented videos for a movie night (I think Anaconda was the pick that finally got my video-choosing license suspended for a while). It's not so much that I have bad taste, but I'm usually a sucker for an intriguing idea, however poorly executed, or an exotic setting, however dull the action taking place there. With this disclaimer up front, I've put together a list of the top five oddest movies I'm glad I can't forget. By "oddest" here I mean both that the movie concept itself was oddly unique, and that it's odd the movie should have etched itself into my imagination the way it has.

(On a side note, in his book Through a Screen Darkly, Jeffry Overstreet talks eloquently about the spirituality of films, and the unique way in which this particular art medium can act as a window onto the divine. While only one of the movies here makes it to his 200+ list of spiritually thought-provoking films, I think each of them in its own way raises spiritual themes that the Christian Faith might speak to.)

5. Meetings with Remarkable Men. Directed by Peter Brook (1979). Hands down one of the strangest movies I've ever seen. Based on a semi-autobiographical book by an obscure Greek-Armenian mystic named G. I. Gurdjieff, the film is a fragmented series of episodes and dialogues that traces Gurdjieff's journey through Central Asia looking for spiritual enlightenment and esoteric knowledge. It culminates with his initiation into a mysterious brotherhood of mystics. I had a friend in university who was a self-styled Gurdjieffian searching for esoteric knowledge himself, and who roped me into watching it with him. I wish I had known then what I know now: that in Christ, God's hidden wisdom and knowledge have been made public in the open scandal of the cross (Col 2:1-3). What talks we might have had then.

5. Meetings with Remarkable Men. Directed by Peter Brook (1979). Hands down one of the strangest movies I've ever seen. Based on a semi-autobiographical book by an obscure Greek-Armenian mystic named G. I. Gurdjieff, the film is a fragmented series of episodes and dialogues that traces Gurdjieff's journey through Central Asia looking for spiritual enlightenment and esoteric knowledge. It culminates with his initiation into a mysterious brotherhood of mystics. I had a friend in university who was a self-styled Gurdjieffian searching for esoteric knowledge himself, and who roped me into watching it with him. I wish I had known then what I know now: that in Christ, God's hidden wisdom and knowledge have been made public in the open scandal of the cross (Col 2:1-3). What talks we might have had then.

4. Walkabout. Directed by Nicholas Roeg (1971). The story of two British schoolchildren, abandoned in the outback of Australia and befriended by a silent aboriginal boy on walkabout who helps them survive. With a lot of surreal, dream-like footage of the Australian landscape, and a lot of drawn-out, wordless interactions between the three children, it asks a lot of the audience, and the ending is anyone's guess. It struck me at the time as a kind of "return to Eden/back to innocence" story wrapped up (ironically) in a poignant and painful coming of age story. Maybe it's the kind of back-to-Eden story we should hear more often.

4. Walkabout. Directed by Nicholas Roeg (1971). The story of two British schoolchildren, abandoned in the outback of Australia and befriended by a silent aboriginal boy on walkabout who helps them survive. With a lot of surreal, dream-like footage of the Australian landscape, and a lot of drawn-out, wordless interactions between the three children, it asks a lot of the audience, and the ending is anyone's guess. It struck me at the time as a kind of "return to Eden/back to innocence" story wrapped up (ironically) in a poignant and painful coming of age story. Maybe it's the kind of back-to-Eden story we should hear more often.

3. Joe vs. The Volcano. Directed by John Patrick Shanely (1990). Though this is probably the one movie Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan would like to call a mulligan on, I found something strangely appealing about this campy story of a man's journey to find his inner hero. A satire of western capitalism, an allegory about the modern search for meaning, a quest story about finding inner wholeness by confronting our fear of death, it asks the kind of questions about the spiritual life that Christians should be engaging, I think, with the answers of Christ. (You can click here for a hypertext film-study I designed for teaching this movie in my grade eleven English classes.)

3. Joe vs. The Volcano. Directed by John Patrick Shanely (1990). Though this is probably the one movie Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan would like to call a mulligan on, I found something strangely appealing about this campy story of a man's journey to find his inner hero. A satire of western capitalism, an allegory about the modern search for meaning, a quest story about finding inner wholeness by confronting our fear of death, it asks the kind of questions about the spiritual life that Christians should be engaging, I think, with the answers of Christ. (You can click here for a hypertext film-study I designed for teaching this movie in my grade eleven English classes.)

2. Far Away, So Close. Directed by Wim Wenders (1993). A film about fallenness and grace and incarnation, it tells the story of an angel who becomes human in an instant (to save a boy falling off a balcony), and who then finds himself on a quest for experience and redemption in his new life in the flesh. Apparently angels can only see in black and white, and can hear everyone's thoughts at once, which makes for some pretty evocative scenes moving in and out of colour with all sorts of mumbled lines in different languages coming at you all at once. It's the kind of film you could wear your beret to if you want.

2. Far Away, So Close. Directed by Wim Wenders (1993). A film about fallenness and grace and incarnation, it tells the story of an angel who becomes human in an instant (to save a boy falling off a balcony), and who then finds himself on a quest for experience and redemption in his new life in the flesh. Apparently angels can only see in black and white, and can hear everyone's thoughts at once, which makes for some pretty evocative scenes moving in and out of colour with all sorts of mumbled lines in different languages coming at you all at once. It's the kind of film you could wear your beret to if you want.

1. Babette's Feast.Directed by Gabriel Axel (1987). Critically acclaimed and demonstrably brilliant, this is the only movie on this list that I would endorse as a must see. It tells the story of Babette, an extraordinarily gifted chef de cuisine and Parisian restaurateur who has been living incognito as a simple cook to two elderly sisters in a small, rustic fishing village in Denmark. When Babette wins 10,000 francs in a lottery, rather than return to Paris, she choses to spend the money on a lavish banquet for the villagers. Though they are woefully ignorant of the luxury they are being treated to, a spirit of genuine fellowship settles over them through the course of the meal, exposing and healing some deep-rooted hurts and bitterness in the community. Funny, moving, and evocative, this film asks powerful questions about the spirituality of food, and table-fellowship, and hospitality and art (and for the Christian, it also suggests poignant questions about the meaning of the Eucharistic meal, where Christ invites his community to find reconciliation and healing at a table laid with the extravagant feast of his own poured-out life).

1. Babette's Feast.Directed by Gabriel Axel (1987). Critically acclaimed and demonstrably brilliant, this is the only movie on this list that I would endorse as a must see. It tells the story of Babette, an extraordinarily gifted chef de cuisine and Parisian restaurateur who has been living incognito as a simple cook to two elderly sisters in a small, rustic fishing village in Denmark. When Babette wins 10,000 francs in a lottery, rather than return to Paris, she choses to spend the money on a lavish banquet for the villagers. Though they are woefully ignorant of the luxury they are being treated to, a spirit of genuine fellowship settles over them through the course of the meal, exposing and healing some deep-rooted hurts and bitterness in the community. Funny, moving, and evocative, this film asks powerful questions about the spirituality of food, and table-fellowship, and hospitality and art (and for the Christian, it also suggests poignant questions about the meaning of the Eucharistic meal, where Christ invites his community to find reconciliation and healing at a table laid with the extravagant feast of his own poured-out life).

Every Nation, Tribe and Song

The other day my kids told me about this fascinating cross-cultural experience they had at school. Apparently a touring group that played traditional instruments from the highlands of Japan treated their school to a concert.

At least they thought it was Japan. The geographic details were a bit hazy, but what stood out with crystalline clarity for them was the fascinating array of musical instruments. Things my kids had never imagined before: a bowed instrument you played by stretching, a stringed instrument you held in your teeth and played by changing the shape of your mouth. My kids were mesmerized, by the sounds of things.

And they got me thinking about ethnodoxology.

Ethnodoxology is one of those ten-dollar words I learned in seminary; it means something like "the study of ethnic worship," and it looks at the use of indigenous musical traditions in Christian worship. It's really a vital issue for global missions these days, I think, because as our global village continues to shrink, indigenous musical forms are being pushed out of the village church in many parts of the world, to make room for contemporary (read: western) Christian music. My theology of worship prof came home from a teaching trip to India not long ago, lamenting the fact that he had to scour the city of Secunderabad to find a church that still used indigenous musical forms. Most had gone CCLI.

More's the pity, too, because there's a wonderful diversity of musical traditions that might enrich the global church's worship if we had ears to hear it.

More's the pity, too, because there's a wonderful diversity of musical traditions that might enrich the global church's worship if we had ears to hear it.

About six or seven years ago (before I ever learned the word ethnodoxology) I developed a curious fascination with musical instruments from different cultures. What started with the gift of some instruments my Grandfather brought home from a missions trip to Africa eventually grew into a modest collection of instruments from around the globe. Some of the more exotic ones in my collection (pictured left) include a kora--a

So one day, after researching and experimenting with these different instruments for a while, and after daydreaming about all the Christ-claimed, blood-bought cultures they represented for a longer while, I tried to write a worship song that included as many of them as I could play passably. To make it sound even less "western," I wrote it in 5/4 time; you can click here to listen.

May the Lord hasten that day.

(If I've piqued your interest in ethnodoxology on a more academic level, you can read an interesting study posted here at the Canadian Centre for Worship Studies.)

Labels: eschatology, music, songwriting, worship

Kierka-palooza?

Speaking of rock music and existential Danish philosophers... a while ago I was reading an essay by Kierkegaard called "Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing," a meditation on single-mindedness and the life of authentic faith. In typical Kierkegaard fashion, he kind of lost me along the way, but the title echoed around in my head for a long time. Eventually it came out of me in the form of a musical meditation.

Speaking of rock music and existential Danish philosophers... a while ago I was reading an essay by Kierkegaard called "Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing," a meditation on single-mindedness and the life of authentic faith. In typical Kierkegaard fashion, he kind of lost me along the way, but the title echoed around in my head for a long time. Eventually it came out of me in the form of a musical meditation.

Maybe to balance out the reflections on culture, rock n' roll and drinking tunes I shared in my last post, I thought I'd offer it here. [click here to listen]

Rock me Mr. K!

Labels: music, songwriting

A "Jug O' Punch" in Church?

Did you ever get that mass email that warns you not to flash your lights at an oncoming car with their high-beams on, because of a new "gang initiation ritual" where initiates to some enigmatic (probably Asian) gang drive around with their high-beams on and are required to chase down and shoot the first motorist who signals them like this?

It's an urban myth.

Or how about the one about the man who follows a beautiful seductress home from the bar, only to wake up, one or two spiked-drinks later, shivering in a bathtub full of ice with mysterious stitches in his side and a note (maybe written in lipstick on the mirror, for effect) explaining that one of his kidneys was surgically removed while he lay anesthetized, to be sold on the organ-donor's black market?

Urban myth.

I once heard some sociologist suggest that urban legends like these are actually significant narrative acts whereby a social group tries to justify its deepest cultural anxieties by framing them in outrageous stories that are just plausible enough to need no substantiation. The gang initiation myth, for instance, allows us to justify our irrational xenophobia; the stolen kidney allows us to narrate our anxieties about the dangers of promiscuity, or our suspicion of the mysterious powers of modern medicine.

The Faith, of course, has its own versions of these narrative acts. Heard the one about the unassuming first-year college student who calmly refuted the belligerent professor of evolutionary biology or nihilistic philosophy using nothing but cool reason? Or how about the one about some high-tech space-clock at NASA that inexplicably discovered a missing day in the chronology of the solar system and thus inadvertently proved Joshua 10:13?

Christian-urban myths.

But here's another Christian urban myth you might have heard. It usually comes up when people in the church are asking questions about whether the latest rock-music style is appropriate for worship. At some point someone quips that, after all, Luther used bar songs for the melodies of some of his greatest hymns; if Luther could use drinking songs, surely a bit of fuzz on the electric guitar shouldn't turn heads.

But here's the thing. Although the hymnals of the Reformation were indeed criticized for their rollicking rhythms, there's no evidence that Luther ever used bar tunes for his hymns. In fact, as far as we know, the only time he actually used a secular folk tune, he ended up changing the tune because of its worldly associations. (Here's some hard data from the Works of Martin Luther: of Luther's 37 chorales, 15 were tunes he composed himself, 13 came from Latin service music, 4 were German religious folk songs, 2 were pilgrimage hymns, 2 are of unknown origin, and only one came from a secular folk song.)

Some music historians suggest that the legend about Luther using drinking songs comes from the fact that most of his hymns follow a musical pattern known (coincidentally) as a "bar form."

Luther didn't use bar songs, he wrote his songs in "bar form."

Now, to be clear: this is not a post about whether or not rock music belongs in church. But it is a post about the stories we tell ourselves to narrate and validate our irrational anxieties. And I wonder: are there anxieties about our relationship to culture as Christians that a myth like "Luther used drinking songs" narrates for us?

I'm just thinking out loud here, but could it be that, musical styles aside, there's this niggling thought in the back of our mind that in some way, on some level, we've acquiesced to the worst of culture-- it's glare, it's wealth, it's power-plays, maybe-- in ways we feel we need to justify?

And maybe an urban myth-- like the one about the great Church reformer who used his culture's drinking songs to revamp the church's worship-- helps us do this.

.jpeg)